Keeping the Light On

by Blair Hedley

You've seen them on greeting cards, you've seen them on the movie screen, and maybe you've even glimpsed one from a boat's deck. But though most people know, at least vaguely, what lighthouses look like and what they do, few understand how important they are. What is the purpose of these lone outposts of civilization? And what tasks are assigned for the hardy men and occasional women who staff them?

I've worked at these places, on and off, for the past five years. The paperwork says I'm a "relief keeper," which means that whenever a year-round keeper needs to temporarily leave a station, I'm one of the people sent in as a replacement. I'm never completely alone; there's a rule that each station must have at least two keepers present-a senior or acting senior, and a junior. This is a skeleton crew, because another rule is that if the station's boat is launched, two people must be on board, while one remains on the station.

Nootka Lighthouse

The word "Lighthouse" is a layman's term; in the coast guard's jargon, they're called "lightstations," or simply "lights." Most of British Columbia's 27 manned stations have no roads nearby, so moving from place to place is something of an adventure. Casual employees, travelling light, are shuttled around by helicopter, while full-time keepers moving to or from stations are sometimes carried on Canadian Coast Guard ships. Norbert Brand, who has worked at the Cape Beale lightstation outside of Bamfield for thirty years, recalls his treatment by the ship's crew on one such journey: "I thought they were wonderful, actually. Good food, definitely, and the scenery was nice."

A keeper's most important job is to aid mariners in trouble. Mark Tiglmann, who recently became the acting senior keeper at Nootka Light, remembers an incident in the summer of 2007, when he and his then-senior answered a distress call.

"It was a couple of old fellows that had clogged-up fuel filters. We motored over there, and found these people just ready to go up onto the rocks. It was a bit windier than when we had left the station, and these gentlemen had thrown their anchor overboard, and their motor was just feet from the rocks. It was too tight to get in too close to the rocks and whatnot, so we actually threw them a line, and so we towed them into calmer waters and proceeded to try and get their engines up and running. We ended up finally dumping gas [into the tank] and trying to get their engine re-primed, and after several tries at getting this thing going, it finally flashed [up]."

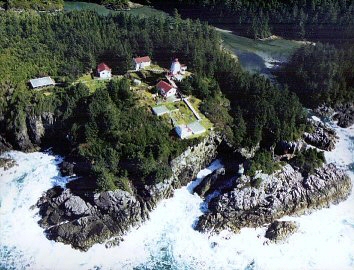

Overhead shot of Cape beale lighthouse

Not all rescue operations are so fortunate. Brand recalls a capsized fishing vessel that drifted near Cape Beale in December of 1995.

"You could smell the diesel fuel. The lifejackets were just floating. I alerted the Bamfield lifeboat to come out, and they alerted the American helicopters to come up the coast from Port Angeles to do search and rescue. The sea condition was horrendous, was just wild out here. I think they turtled just past Pachena [Point], and abandoned the vessel, and they got into Dead Man's Cove-two of the survivors-and one unfortunately got killed on landing. One guy was tossed out of the life raft, and went swimming for Beale-he was a local guy-he never made it ashore, either. But the other guy actually made it ashore, and was picked up by the American Coast Guard helicopter. You always hope that you'll find them alive, but sometimes it just doesn't happen that way."

A less deadly but more frequent source of drama is the station's supply of potable water. Each keeper's house is built with a system that collects rainwater from the roof and stores it in a large concrete cistern. On the way to the tap, it goes through a series of filters to make it potable. Every drop is precious, so new keepers quickly learn to be conservative with their water, especially during dry months. Mark saves the water used when boiling potatoes in order to water the plants that he and his wife cultivate to provide fresh vegetables between supply ship visits. Most annoying to visiting city-dwellers is the rule that flushing urine in the summer can be out of the question, at least until the smell becomes bothersome.

Mark has heard stories of some keepers using a hose to siphon water from their co-workers' cisterns. But he doesn't know "Whether they're just rumours, or the whole psychology of the lights-the things that go on in your head, thinking that "Jeez, I didn't use my water; someone else must have.""

Many think that the entire station is housed inside the light tower. In fact, keepers almost never enter the towers. Besides the iconic lights, each station consists of an engine room, which is a soundproof building housing the big diesel generators that provide power; the radio room, which houses the complex radiotelephone equipment; several bulk diesel tanks; an antenna array of some kind; a landing platform for helicopters; a tool shed; and two decent-sized houses for the keepers and their families. Optional buildings include a garage, a boathouse, a dock, a workshop, a spare house for relief keepers, and a derrick or highline mechanism for hauling cargo to or from Coast Guard work boats.

Cape Beale lighthouse

The high point of the month is the supply run, known as "the tender" in Coast Guard jargon. Once a month, every keeper sends an e-mail to the nearest coast guard base that fields helicopters. The message lists the food and supplies that the keeper thinks will be necessary in the coming month. A coast guard shopper buys the items listed, and sends the keeper an invoice. The supplies are put in boxes, carefully labelled with their destinations, then held, depending on their contents, in either a freezer, a cooler, or a dry storeroom until a helicopter is scheduled to deliver them. Delivery day is much anticipated. Tiglmann describes fresh vegetables as "A luxury item out here. It's something that you can't keep unless you can freeze it or dry it or something. It's no longer fresh when you've done that."

A keeper's day-to-day work mostly involves recording and broadcasting weather reports. Every three hours, from 4:40 a.m. to 10:40 p.m., each station sends a report on the surrounding weather conditions to the nearest coast guard base. These reports are then continuously re-broadcast on a reserved marine radio channel, much to the appreciation of mariners and pilots. Keepers also make records of things like air and ocean temperatures, which Environment Canada uses in its climate calculations.

Because of their isolated locations, keepers are often a few years behind city-dwellers in their means of communications and technology. "Do you get TV?" was, for decades, the most common question asked by a city-dweller meeting a keeper for the first time. Nowadays, it's "Do you get internet?" Limited access to the Internet became possible a few years ago when the Coast Guard made an arrangement with a satellite internet provider. Before that, keepers often maintained their own personal libraries, or paid for satellite TV.

Telephone calls are usually made by cell, or, if the station has a microwave transmitter, by land line. But for years, all calls had to be patched through the coast guard's radiotelephones. This amounted to one big party line; nothing prevented radio operators and other keepers from hearing every word.

There is no life quite like it. The job requires a certain type of mind-one that does not become lonely despite long stretches of aloneness; is capable of constant vigilance; and is proactive enough to solve sudden, unexpected problems. It's an unusual mix of work and lifestyle, perhaps best summed up with a quote more often applied to 7-11 stores: we're not always busy, but we're always open.