Cowichan Valley Gothic

by Ashley Gaudreault

I haven't pictured myself in overalls in awhile. In fact, I threw every pair I had away years and years ago. Don't own a pitchfork either. Not even a small shovel. Going to need some gloves, probably a rake too. Have to fork over some cash for seeds and add a couple buckets to my list. Maybe try to find some gardening advice.

Judy Stafford might just end up being my savior. She's the coordinator of my hometown, Duncan's, community gardens group. My roommate and I have talked to her about trying our hand at growing our own vegetables. But before we give it a try and attempt the heavy labouring garden pertains, Stafford fills me in on what Duncan's community gardens are all about.

I'm disappointed to find out there's a huge waitlist to get a chunk of land, Cowichan's gardens are so popular this year's plots are already called for. According to Stafford, who's the executive director of Cowichan Green Community (CGC), there are a ton of people like Jen and I with the same idea. Fortunately, CGC regularly hears from people willing to let their land be used for a community garden, so there's hope for Jen and I yet.

For inspiration, I visit CGC's primary community garden site, Kinsmen Park. The park is located on a residential road and is surrounded by apartment buildings. Kid's cries waft over from a nearby playground. There are 18 plots enclosed by a chain-link fence. Each garden box is unique. Some are weed-stricken, others look to have been mastered by a green thumb. People have planted lettuce, strawberries, rhubarb and a variety of herbs.

Gardens cultivate community and peace among people and captivate community spirit, believed landscape architect, psychologist, educator and community activist Karl Linn. Linn was also known for inspiring and guiding the creation of "neighborhood commons" on vacant lots in East Coast inner cities from the 1960s through to the 1980s. In the 1990s he found himself another calling: community gardens. Some of his community gardens were devoted entirely to creating ecological green spaces or habitats, and for growing flowers; others provided education or access to gardening to those who otherwise could not have a garden.

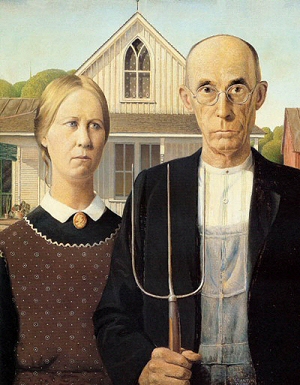

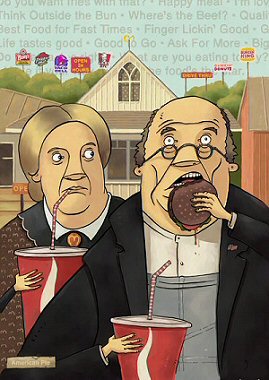

That's where people like Jen and I come in. We're both extremely grateful our community is able to provide us with space. As the anticipation builds and thoughts puree in my mind—besides creating checklists of what I need to start the garden and talking with friends about my new venture—I can't help but picture the good ol' American Gothic painting with Jen and I standing in for the old folks, staring solemnly before the painter.

We could add also a co-worker of mine to that vision as well. Her name is Sarah Simpson and, though she isn't going to be growing a garden with us, she is trying what's said to be extremely hard to do in the Cowichan Valley: grow grain. Simpson says she spent Sunday raking the 200-square foot plot she got a hold of at Makaria Farm in Duncan. "There's something really special, primal even, about growing your own stuff," she says. "Whether it's grains or vegetables, it's a really an empowering feeling."

Kinsmen Gardens

Like Jen and I, Simpson lives in an apartment and that's why she decided to look for a place she could borrow land. "This grain growing exercise is a good first step toward taking control of my own personal consumption," she says. "There are many reasons to grow your own food and it seems new reasons pop up every day. Global food shortages and high costs of transportation, not to mention the closer it's grown to your table, the less chemicals that need to be used to preserve it."

With a good number of eager souls like Sarah, Jen and I, the Cowichan Valley seems to have a very green consciousness which may be one of the reasons why the community garden concept is taking off so well.

"There is a general interest surging through the community now," Stafford says. "We had 30 people come and help at the Harvest Festival we held last September. Our board members are volunteers and there are about 10 active ones. Overall, the concepts of what we are doing are well received. There is a lot of interest and media coverage around food security as attested by the hundreds of people who attended the Seedy Saturday we organized in less than two weeks."

Stafford, a 48-year-old ex-banker, moved to Duncan in 2006. "I was freelance writing at the time and applied for a position at CGC in December of 2007 as there was a strong writing component. I have had several gardens, and lived on a farm for four years, gardening a half acre and working on a farm part-time, helping with a Community Supported Agriculture program. I have always been environmentally conscious. I am a vegetarian, live a minimalist lifestyle and generally try to remain conscious of the planet," she says. "Since becoming the executive director in September 2008, I have tried to raise CGC's profile. This is mostly through joining other committees, attending events and promoting CGC through the media."

Community Gardens

Established in 2001, CGC promotes food security through several community projects, including the gardens, the first of which opened in 2002. They also sell Salt Spring Seeds, host workshops and do promotions and other activities relating to food security and sustainable gardening. To CGC, food security means all members of a community at all times have access to nutritious, safe, environmentally sustainable, or culturally acceptable and accessible food obtained through normal distribution routes. CGC has developed "The Cowichan Food Charter," plan which was designed to reduce the barriers and restrictions to local food production. According to CGC's website, the Charter acts like a set of guidelines for local governments and citizens to enhance food security.

Back in 2002, CGC identified potential sites for their first garden. Their priority was a spot at Centennial Park as it's only a few blocks from Duncan's City Hall. After collective energy went into posters, community meetings and door-to-door banging, there now is a committee of volunteers who have taken over the responsibility of the Centennial Park Garden.

The Kinsmen Park Garden, CGC's main focus, has 18 beds and one shared bed. The City of Duncan has been extremely supportive of the project since day one and just gave approval for it to expand. The cost to join is only $20 per person, which doesn't break the bank for Jen and I. The cost to the CGC, however, is quite a bit more: about $13,000 to start up the Kinsmen site's 18 beds. Last year, the organization gathered donations from the community to cover the bill. Stafford hopes to be as lucky this year.

There are several other community garden advocates working to secure sites in areas outside of Duncan as well. In Lake Cowichan, a 20-minute drive from Duncan, the town council recently approved a piece of land where a group of volunteers will develop a neighborhood garden. Honeymoon Bay, a tiny lakeside community 15 minutes north of Lake Cowichan, has had one for several years.

Stafford says community gardens aren't just a go-green trend either. "It's not a concept that is going away-quite the opposite. It can work in any community."

Community gardens got big after the World Wars. "During and after both World Wars, community gardens provided increased food supplies which required minimal transporting," says the website CityFarmer.org. "During the Great Depression, city lands were made available to the unemployed and impoverished by the Work Projects Administration (WPA); nearly 5,000 gardens on 700 acres were cultivated in New York City through this program."

People in the United States have also delved into the community garden movement. Even Michelle Obama planted a garden at the White House. The First Lady and students from Washington's Bancroft Elementary School broke the ground for the White House Kitchen Garden on the South Lawn of the White House this spring. The students involved will watch as it produces healthy vegetables to be cooked in the White House Kitchen and given to Miriam's Kitchen, which serves the homeless in Washington, DC.

Stafford says a community garden is successful and healthy by definition. "It's community coming together, sharing space, working, producing healthy food and interacting. When people work together in a like-minded project, the energy is phenomenal. People know they are helping each other and the planet, and the benefits are very high."

According to Stafford, anybody can be a gardener, even people like me who don't have a hint of experience. You can start anywhere there's land. "You don't need to build raised beds. You don't need much equipment either. You can use existing soil." Compost, though, says Stafford, is critical to setting up a good growing environment. And, of course, you need seeds or seedlings to start. Participants grow a wide variety of things, from root crops to regular greens, vegetables and grains.

Stafford says she's not an expert on what grows best here, but does advocate the Gardens' importance and encourages people to join.

"It's just a lot of fun," says Stafford. "People have a great time doing it and I'm sure you and your roommate will too."